Sustainability Draft Supplementary Planning Document

(1) 2 Objectives

(3) Climate Change Mitigation

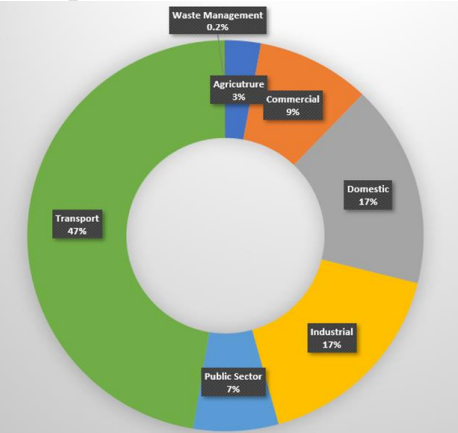

The UK is expected to experience warmer, wetter winters and hotter, drier summers with more frequent weather extremes as a result of climate change[2]. The highest emissions scenario predicts that summer temperatures in the UK could be 5.4°C warmer[3] by 2070 with average summer rainfall falling by 47%. Winters could be up to 4.2°C warmer, with up to 35% more rainfall.

The Climate Change Act 2008 provides an overall framework for climate change mitigation and adaptation action across the UK. It sets a legally binding goal of reducing UK greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 100% from 1990 levels (Net Zero) by 2050.[4]

NHDC declared a climate emergency in May 2019 pledging its commitment to achieve carbon neutrality for the Council's own operations by 2030 and to achieve a Net Zero District by 2040. NHDC's Climate Change Strategy 2022-2027 sets out how the Council will reduce its own carbon emissions to achieve a carbon neutral position by 2030 and what actions it will undertake to achieve a net zero carbon district by 2040.

The Tyndall Centre produced[5] an estimate of North Herts 'fair contribution' towards the Paris Climate Change Agreement, recommending that the District:

- Stays within a maximum cumulative carbon dioxide emissions budget of 4.2 million tonnes (MtCO2) for the period of 2020 to 2100 by achieving average mitigation rates of CO2 from energy of around -13.5% (minimum) per year.

- Initiates an immediate programme of CO2 mitigation to deliver the above cuts in emissions in order deliver a Paris aligned carbon budget. Zero Waste

- Reaches zero or near zero carbon no later than 2041. The report provides an indicative CO2 reduction pathway that stays within the recommended maximum carbon budget of 4.2 MtCO2.

- In 2041 5% of the budget remains. Earlier years for reaching zero CO2 emissions are also within the recommended budget, provided that interim budgets with lower cumulative CO2 emissions are adopted.

In order to achieve the above the report recommended that the District:

- Seriously consider strategies for significantly limiting emissions growth from aviation and shipping.

- Promote the deployment of low carbon electricity generation within the region.

- Manages the Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) sector to provide CO2 sequestration where possible.

(1) Zero Waste

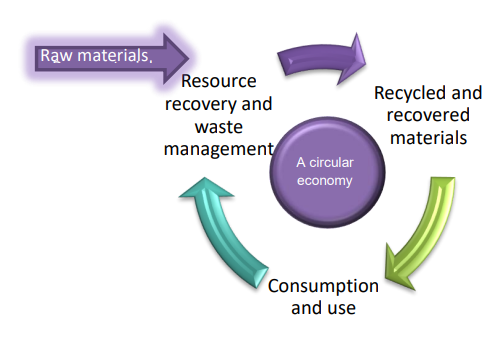

Household, commercial and industrial, construction and demolition waste have economic and environmental consequences. Disposal of plastic, food and garden waste can release greenhouse gases, which contribute to climate change. The government's 'Our waste, our resources: a strategy for England' (2018) sets out a strategy for preserving material resources by minimising waste, promoting resource efficiency and moving towards a circular economy where products are reused and recycled (Figure 2). The Environment Act 2021 sets out a target of 50% reduction in the amount of residual waste (excluding major mineral waste) produced per person in England by the end of 2042, from 2019 levels.

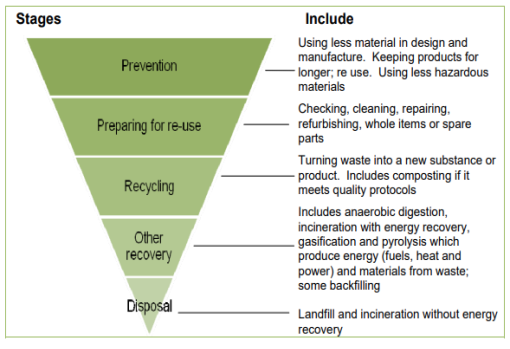

Figure 2 - The Circular Economy, Figure 3 - The Waste Hierarchy (DEFRA)

The Hertfordshire Waste Development Framework sets out the spatial vision and strategic objectives for waste planning in Hertfordshire up to 2026. It seeks to achieve net self-sufficiency (to deal with the county's own waste) and to maximise recycling, recovery and processing of waste to minimise the amount of waste sent to landfill.

NHDC follows the principles of the waste hierarchy giving top priority to preventing waste in the first place. When waste is created, it gives priority to preparing it for re-use, then recycling, then recovery, and last of all disposal (e.g. landfill) as illustrated in figure 2.

To help achieve North Herts net zero targets, development proposals should seek to minimise the amount of waste from new development going to landfill. This can be achieved by working closely with the Council to deliver innovative, efficient waste management systems that maximise waste recycling.

(3) Carbon Footprint

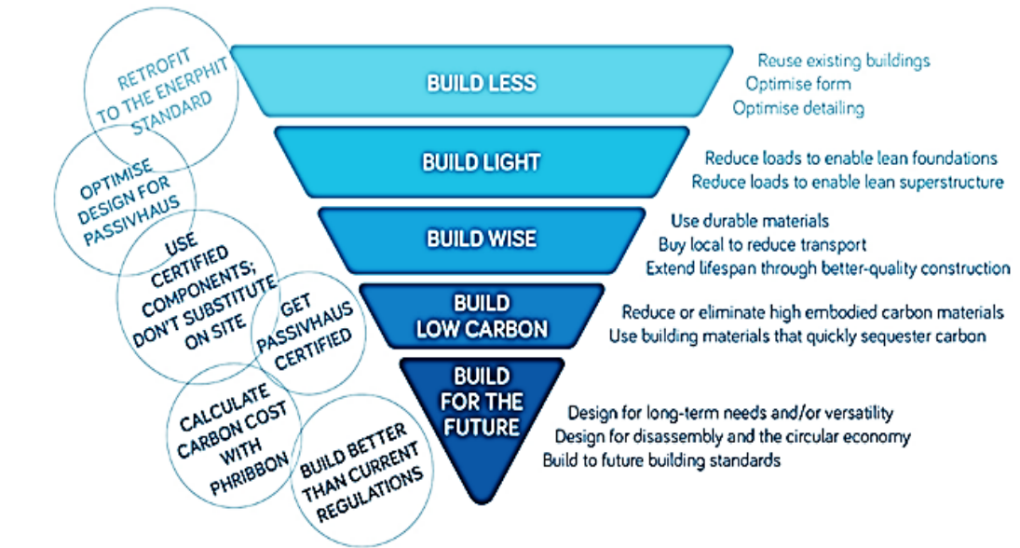

Construction and demolition activities are some of the largest consumers of raw materials and produce substantial waste and emissions. Embodied carbon refers to the energy consumed in manufacturing, delivering, and installing the materials used to build, refurbish and fit-out a building, and its eventual decommissioning/ disposal at the end of its life. This includes emissions associated with fuel used to generate energy and those released in the production of materials like cement. In reduce embodied carbon development should be based on efficient design optimised to reduce loads to enabling leaner foundations and steel structures, reducing the cement content used, using alternative materials such as masonry instead of concrete blocks and clay fired bricks, using timber framing and specifying materials associated with lower carbon footprint. Additionally the design should consider factors such as durability and adaptability and the disassembly and re-use at the end of life.

Figure 4 - Reducing embodies carbon (Passivhaus Trust)

New developments should incorporate circular economy practices and aim to achieve net zero waste as far as practicable. This can be achieved through modern methods of construction (MMC) and design for manufacture and assembly (DfMA)[6] processes and following the waste hierarchy. It is also important to consider the lifetimes of the various elements or 'shearing layers'[7] of buildings. Elements with the shortest lifetimes (e.g. finishes, and furnishings) should ideally have minimal negative environmental impacts and embodied carbon so they can be renewable. Elements with longer lifetimes (e.g. building structures) may require more embodied carbon, but their associated negative environmental impacts may be minimised by designing these layers for the greatest degree of durability[8].

In summary achieving low/ zero embodied emissions will require:

- Optimising design with the aim of reducing the raw materials used through design optimisation and the use of low/ zero carbon products.

- Reuse: utilising recycled materials, re purposing of existing buildings/ structures and designing buildings for deconstruction and re-use.

- Sequestration: incorporating measures to sequester carbon and using alternative material such as wood or recycled concrete products. For example, substituting wood for steel and concrete has the potential to greatly reduce the GHG impact of buildings, especially if the wood structure can be salvaged at the end of its life and reused. Also landscaping can be designed to sequester carbon through appropriate planting.

(1) Operational Carbon

Operational carbon refers to the amount of carbon emissions associated with the building's annual operation. This includes electricity, gas and other fuels used in a building for heating, cooling, ventilation, lighting, hot water, appliances, and computer servers in commercial premises. Developers are encouraged to follow a fabric first approach such as LETI or Passivhaus standards, aiming for net zero carbon; where energy on an annual basis would be zero or negative. For the operational carbon emissions of a building to be zero, it must be highly energy efficient and powered by renewable energy either on or off-site, with any remaining annual carbon emissions offset. Further information is provided in the draft Hertfordshire Development Quality Charter.

(3) Whole life carbon

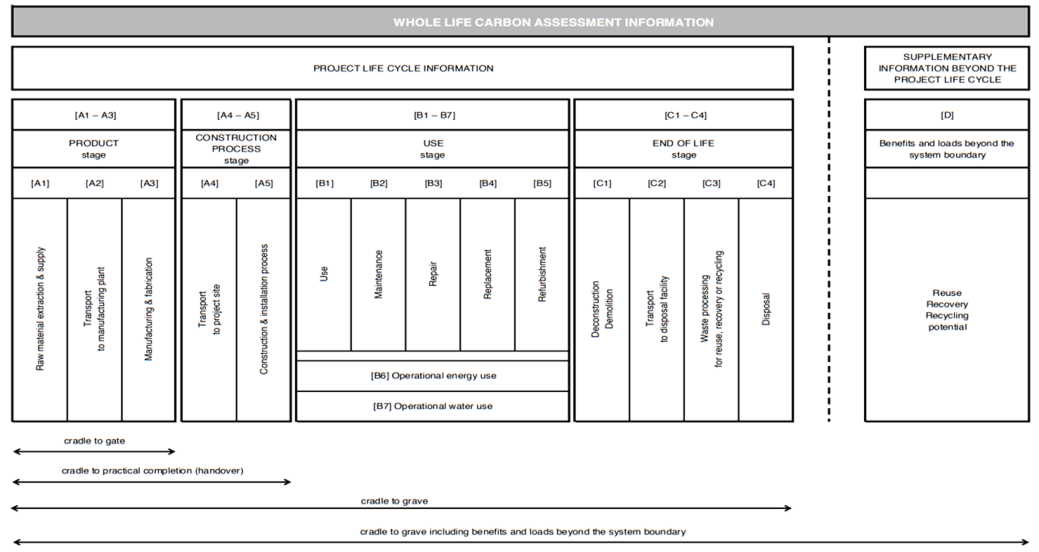

Whole life carbon (WLC) emissions are the total carbon emissions resulting from the construction and the use of a building over its entire life, including its demolition and disposal. They capture a building's operational carbon emissions from both regulated emissions (due to fixed building services, as defined in the Building Regulations such as lighting, heating, hot water, air conditioning and ventilation) and unregulated energy (e.g. emissions relating to cooking and electrical appliances), as well as its embodied carbon emissions (emissions associated with raw material extraction, the manufacture and transport of building materials, and construction; and the emissions associated with maintenance, repair and replacement, as well as dismantling, demolition and eventual material disposal). A WLC assessment also includes an assessment of the potential savings from the reuse or recycling of components after the end of a building's useful life. It provides a true picture of a building's carbon impact on the environment. British Standard BN EN15978 sets out principles of embodied and whole life carbon measurement in the built environment (Figures 5&6). A template has been produced which applicants will be expected to include at the Pre application stage with updates at subsequent stages of the application process. This should demonstrate how the development will reduce overall emissions.

Figure 5 - Whole life carbon emissions

Figure 6 - Whole life carbon assessment (BS EN15978)

(7) Land use & wildlife

North Herts has a wide range of habitats, including hedgerows, wildflower meadows, orchards, ponds, lakes, reed bed and fen, ancient woodlands, chalk streams and a wildlife corridor. Many of these habitats are within designated biodiversity sites, reflecting their value in terms of wildlife interest. These include national designations such as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and Local Nature Reserves (LNR), and local sites such as local wildlife sites (LWS). Additionally, in urban areas green spaces such as gardens, Churchyards, parks and allotments also provide valuable habitats that support a range of species and provide stepping stones for biodiversity.

The Environment Act 2021 introduced a requirement for planning applications to provide 10% Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG). It also established the requirement for Local Nature Recovery Strategies (LNRS); a new mandatory system of spatial strategies that will create a national system of interconnected sites for nature.

Residential and non-residential developments have the potential to produce detrimental effects on wildlife and biodiversity through encroachment and recreational disturbance. The NHLP seeks to address this by focusing growth within existing key settlements and utilising brownfield/ previously development land where possible. Where strategic development is allocated on greenfield land, the Plan includes policies seeking to mitigate potential adverse impacts on the environment. This is also part of the NHLP's vision which states 'the rich biodiversity and geodiversity of North Herts will have been protected and enhanced where possible. Where new development could potentially have an adverse impact on biodiversity and geodiversity, measures will have been taken to ensure that the impact was either avoided or mitigated' and 'new green infrastructure will have enhanced the network of green corridors linking settlements to the open countryside, providing greater opportunities for healthy lifestyles.' The Plan seeks to protect wildlife habitats and deliver biodiversity net gain. In this context the following strategic objectives are particularly relevant:

- ENV3 – Protect, maintain and enhance the District's historic and natural environment, its cultural assets and network of open spaces, urban and rural landscapes.

- ENV4 – Reduce water consumption, increase biodiversity and protect and enhance the quality of existing environmental assets by enhancing new green spaces and networks of green space for both recreation and wildlife.

- NE4 – Development to deliver measurable biodiversity net gain and to contribute to the restoration of ecological networks and degraded or fragmented habitats. Applicants are required to submit an ecological survey commensurate with the scale, location of development and its likely impacts on biodiversity demonstrating that adverse effects can be avoided and / or minimised according to the mitigation hierarchy. Net gains can be delivered through soft landscaping and tree planting to support wildlife habitats as identified in the Hertfordshire Biodiversity Action Plan.

- NE1 – seeks to protect the existing Green Infrastructure (GI) network and the creation of new strategic GI where appropriate. This is also the objective of SP12 which sets out a hierarchy of designations and features, seeking to protect and enhance designated and non-designated biodiversity sites in accordance with their position within the hierarchy.

- NE5 and NE6 - seek to protect existing open space and support new and improved provision as part of new development schemes.

The District has a range of nationally and locally designated sites including 7 Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI)[9], 9 designated Local Nature Reserves (LNRs) and over 300 designated Wildlife Sites (LWS). Additionally, there are watercourses including rare chalk stream habitats, woodlands, trees, parks and open spaces are interspersed throughout the District.

The presence, or potential presence, of any protected species such as bats and great crested newts, is a material consideration in planning application decisions. Similarly, there are priority habitats such as deciduous woodland and chalk grassland present within the District.

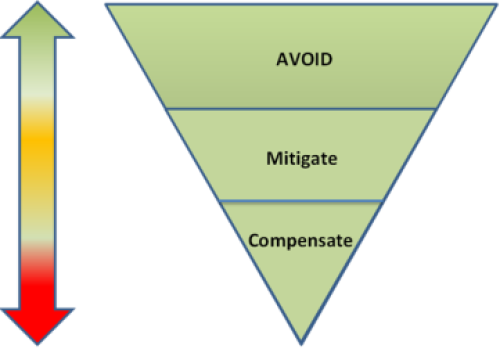

Proposals should avoid habitat loss and enhance the connectivity of ecological networks. The NPPF requires that development proposals follow the mitigation hierarchy (Figure 7).

Figure 7 - The mitigation hierarchy

Therefore, it is important to ascertain if there are important habitats on the proposed site by carrying out an ecological survey of the site. Where important habitat is present, avoidance should always be the first consideration. It may also be possible to avoid harm to existing habitat through careful consideration of alternative siting, layout and scale of development such that the existing natural features that contribute to the biodiversity of the site are retained.

Where avoidance is not entirely possible, appropriate mitigation measures should be implemented. These should be commensurate to the scale of development and the importance and legal status of the habitat affected. Examples include the incorporation of planting to create buffer zones to reduce disturbance, implementing a permeable landscape design helping to reduce habitat fragmentation and linking to the existing GI network. This is further discussed in the 'Planning for Nature' guidance.[10], advice can also be sought from Hertfordshire Ecology.

Offsite compensation should only be considered as a last resort where avoidance and mitigation are not possible. This would involve the creation of offsite compensatory habitat according to a spatial hierarchy where local offsite delivery should be prioritised over delivery outside the District which should only be considered as a last resort.

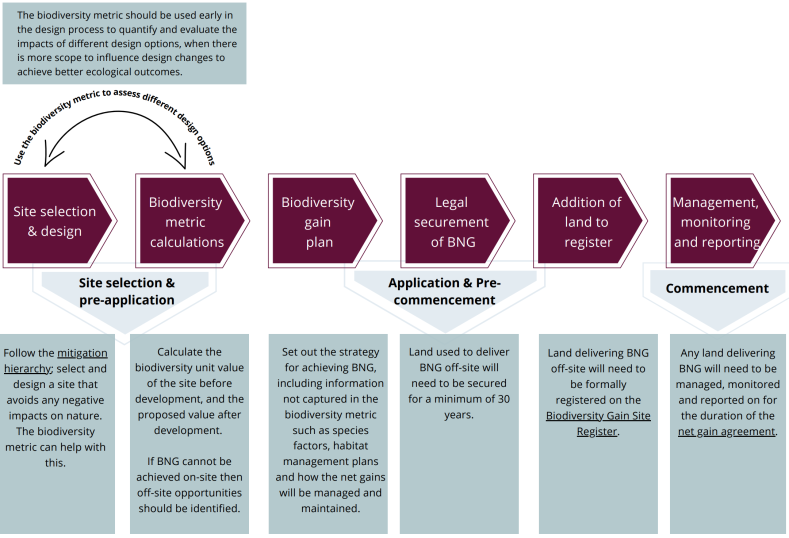

NHLP policy NE4 states that all development should deliver measurable net gains for biodiversity. This requirement is set to a minimum 10% mandatory net gain in the Environment Act[11] calculated using DEFRA/ Natural England's Biodiversity Metric. This should be used early in the design process to evaluate the impacts of different design options. Applicants are required to submit a biodiversity gain plan setting out how a development will deliver biodiversity net gain. This should cover the following:

- How adverse impacts on habitats have been minimised

- The pre-development biodiversity value of the onsite habitat

- The post-development biodiversity value of the onsite habitat

- The biodiversity value of any offsite habitat provided in relation to the development

- Any statutory biodiversity credits purchased; plus

- Any further requirements as set out in secondary legislation.

The biodiversity net gain process is illustrated in Figure 9 Biodiversity net gain can be achieved through measures that serve to provide space for biodiversity and create links to local and/ or strategic habitat networks. Good practice examples include the following elements:

- Incorporating wildlife corridors connecting through the development. The design of the development should not interrupt or block wildlife networks;

- The creation of community woodland within development schemes on greenfield sites where appropriate;

- Community food growing projects, community gardens and allotments;

- Green roofs/ walls and water features;

- Incorporating wildflowers to support pollinators;

- Including flowering lawns to provide forage for bumblebees;

- Housing for wildlife: bat boxes, bird feeders, insect hotels, insect hibernation houses;

Figure 8 - Examples of housing for wildlife - Retaining native planting, trees, orchards, hedgerows, newt ponds and streams; and

- Sustainable drainage systems to manage surface water, filter out pollutants in surface water run-off an provide habitats for wildlife.

The Council already require a Preliminary Ecological Appraisal or Ecological Impact Assessment to be submitted with most types of planning applications. These are required to contain a specific section entitled 'Biodiversity Net Gain' (BNG) which must clearly show how the site has been assessed using the Biodiversity Metric (latest version). This will demonstrate the baseline habitat value of the site (pre-development) and the post development habitat value. It is also required to demonstrate how compliance with the BNG 10 good practice principles[12] has been applied as part of the net gain assessment. Further details regarding evidence and reporting requirements is provided in NHDC's Developer contributions SPD.

(1) Herts Local Nature Recovery Strategy

The Government's 25 Year Environment Plan which includes provision for a Nature Recovery Network (NRN) states that recovering wildlife will require more habitat, in better condition and in bigger patches that are more closely connected. As well as helping wildlife thrive, the NRN should be designed to bring a wide range of additional benefits such as:

- greater public enjoyment;

- pollination;

- carbon capture;

- water quality improvements and

- flood management.

Further information pertaining to important habitats and species within the District is provided in the Hertfordshire Biodiversity Action Plan and the Herts Environmental Records Centre (HERC). Further guidance is provided by The Herts Local Nature Partnership (LNP). The BNG Process is illustrated in Figure 9 below.

Figure 9 - The BNG process (Natural England)

(1) Protecting Chalk Streams & Rivers

Development schemes in the vicinity of water bodies can help improve the quality of river habitats through restoration projects to restore internationally important chalk streams in the District. This will benefit wildlife and improve resilience to climate change as droughts become more frequent. This can be achieved for example by reversing historic drainage works to restore naturally meandering channels which reconnect rivers and streams surrounding floodplains[13]. Developers should seek to integrate and enhance natural water courses though sympathetic design aimed at protecting and enhancing the quality of watercourses and harnessing the recreational opportunities they offer where appropriate. This should include the identification of opportunities for de-culverting to enhance heavily modified water bodies[14]. Furthermore, tree planting to enhance tree cover along water courses serves to provide shade and reduce temperatures so that river habitats and species can survive increasingly hot summers.

(2) Checklist

-

Bronze

Silver

Gold

Ecological Survey

Ecological Survey identifying any priority habitat, protected / priority species establishing potential impacts. (BS42020 or DEFRA Biodiversity Metric)

Wildlife housing for bees/ bats, Newt ponds Creation of Wildlife networks

Links to strategic GI network

Management plan outlining mitigation and monitoring measures

Management plan outlining mitigation and monitoring measures

Management plan also includes measures to enhance existing habitat and biodiversity where appropriate.

In addition management plan includes restoration of natural river/ waterbody courses or seeks to enhance waterbody quality where appropriate

Biodiversity Net gain plan

Biodiversity Net gain reporting (as per HNC Developer Contributions SPD) demonstrating 10% BNG

Greater than 10% BNG

Over 30% BNG

12m complimentary habitat buffers around locally and nationally designated sites.

12m complimentary habitat buffers around locally and nationally designated sites.

LWS Enhancement strategy (where appropriate/ applicable) In addition to standard requirements

Conservation/ enhancement to Nationally Designated site (where appropriate/ applicable) In addition to standard requirement

Open space provision/ enhancement and maintenance/ management plan

Open space provision/ enhancement and maintenance/ management plan

Open space provision also seeks to: Enhance nature depleted areas and; Includes features to enhance to biodiversity e.g. such as copses, ponds, ditches, rough area.

Open space sites link to local and / or strategic green corridors (GI) seeking to compliment the Nature Recovery Network by providing habitat connectivity.

(1) Culture and Community

The NPPF recognises that planning plays a role in facilitating social interaction and creating healthy, inclusive communities. Community and recreation facilities, together with green spaces play an important role in enabling people to participate in physical and cultural activities which can help enhance physical, spiritual and mental wellbeing and engender a sense of inclusion and community. It can also reduce crime and create a sense of place enhancing the overall attractiveness and vitality of neighbourhoods. NHLP Policy HC1 seeks to protect existing community facilities and supports the provision of new ones; subject to proposals meeting the criteria set out in the policy. New development should aim to achieve socially, economically and environmentally sustainable communities. Policy SP10 supports the retention of existing community, cultural, leisure, health, education and local retail facilities and the provision of new ones in new development.

It is important for new development to relate to the local heritage and cultural context, both in terms of the built environment and the landscape. Development should conserve and enhance (where appropriate) the significance and setting of local heritage assets and reflect the local vernacular, historical building typologies, the treatment of facades, materials, and architectural styles.

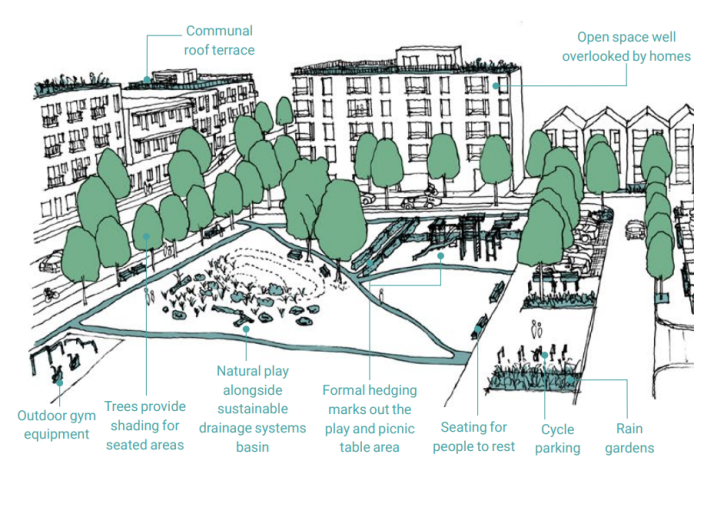

Health and Wellbeing

The built environment has multiple and significant impacts on people's health and wellbeing (Figure 10). It needs to feel safe and secure for all, including the more vulnerable members of the community. It can also positively influence behaviours and lifestyles of residents addressing multiple objectives such as

- improving safety,

- reducing air pollution,

- maximising environmental protection,

- or securing infrastructure investment to attract new residents and a skilled workforce.

Developers and delivery partners are expected to engage health, sport, and physical activity consultees early in the development process to maximise the health and wellbeing benefits of their designs.

The NPPF emphasises the planning system's role in achieving healthy places that enable healthy lifestyles through the provision of accessible green infrastructure, sports facilities, and layouts that encourage walking and cycling. This is echoed in HCC's Green Infrastructure Strategy and NHLP Policy SP9 which seek the provision of accessible, multifunctional GI that supports healthy lifestyles. The Hertfordshire Climate Change and Sustainability Partnership's (HCCSP) Strategic Action Plan for Biodiversity includes several actions seeking to enhance green infrastructure, green space provision and nature based solutions to enhance biodiversity and improve community health.

Figure 10 - Multi benefits of place making and healthy communities (TCPA)

The NHS's 'Putting Health into Place'[15] sets out principles for designing, delivering, and managing healthy places. The following principles are of relevance to designing healthier developments:

- Create compact neighbourhoods: new schemes should facilitate social and economic connections by designing compact, walkable, mixed-use neighbourhoods with distinct identities. Neighbourhoods that do not rely on cars, with attractive streets, parks and community spaces facilitate social interaction and engender beneficial effects on health and wellbeing. Commitment to creating compact neighbourhoods is needed at the earliest stages of planning and development. This should be implemented through a master planning approach informed by the National Model Design Code and NHS England's Healthy New Towns guidance[16].

- Maximise active travel: well-planned neighbourhoods can make walking, cycling and affordable public transport the preferred choice for getting around. Providing appropriate, accessible, infrastructure for whole journeys makes active travel options practical for users. Development should incorporate networks of safe walking and cycling paths with clear signposting, seating and cycle-parking These should link to the wider surroundings, schools, health and local centres. The provision of trails incorporating active play, heritage and nature walks also encourages active lifestyles.

- Foster health in homes and buildings: Provide healthy homes and buildings that are efficient and resilient to climate change. Homes should be designed to have sufficient space (meeting or exceeding Nationally Described Space Standard), daylight levels, ventilation, outlook and privacy. Buildings that are comfortable, offer character and cultivate a sense of community and pride have a positive impact on people's health.

- Enable healthy play and leisure: Development should create opportunities for people of all ages and abilities to come together, be active and enjoy leisure time.

It is important to recognise that some sections of the community face barriers in accessing green spaces and nature (Public Health England, 2020). People living in the most deprived areas, and ethnic minorities are disproportionately affected by high levels of pollution and people in the least deprived areas of England generally enjoy significantly more accessible green space than those in more deprived areas[17]. It has also been shown that, across the older population, a higher percentage of males are active than females[18]. Girls and young women often report feeling unsafe when spending time in public spaces such as parks and green spaces[19] (Figure 11). Development proposals should ensure that nature and landscape are woven into scheme design and careful consideration given to access, visibility, and lighting in order to improve passive surveillance and reduce crime. It is important to consider how people use space, for example women generally feel safest in well-used spaces, obscure, isolated areas create situations of vulnerability. Ensuring that streets, paths and public spaces are well overlooked yet deliver privacy to individual dwellings giving the impression of a high degree of passive surveillance is also helpful in discouraging crime and creating a sense of safety. The inclusion of sensory areas and provision of talking/ tactile maps can help make green spaces more accessible to people with sight impairment.

[3] Compared to the 1981-2000 average

[4] Updated in 2019 in recognition of the 2015 Paris Agreement and following advice from the Climate Change Committee (CCC).

[6] A design approach focussing on optimised design based on off-site pre-fabrications of elements such as floors, slabs and columns for on-site construction. This can lead to less waste generation and a reduction in vehicular transport of materials to site.

[7] Term coined by architect Frank Duffy, the "shearing layers" concept defines buildings as a set of integral components that adapt or change in different timescales.

[8] Reference: Stewart Brand, 1994, 'How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They're Built'. Viking Press.

[9] These are shown on the NHLP policies map: Web Map - LocalPlan (north-herts.gov.uk)

[10] Hertfordshire Local Nature Partnership – Planning for biodiversity and the natural environment in Hertfordshire – guiding principles.

[11] This requirement is expected to come into force in January 2024 for all but exemptions and small sites (residential development of less than 10 dwellings or site area less than 0.5 ha or less. For non-residential development: less than 1000 m2 of floorspace or sites smaller than 1 ha). The transition period for small sites has been extended to April 2024.

[13] Example case studies can be found here https://environmentagency.blog.gov.uk/2023/06/15/working-to-improve-norfolks-chalk-streams/

[16] See Northstowe, Cambridgeshire